Sunlight dapples the little piazza in the centre of Bianco, a downmarket resort on the east coast of Calabria, the "toe" of Italy. From the tables outside a cafe comes the unmistakeable, nasal twang of estuary English. "... very excited," says a woman's voice. Then comes a man's: "... mortgage ... once you've signed ... place of your own in the sun."

Less than 20 paces away, stuck to a wall on the way to the beach, there is a death notice of the sort you encounter throughout southern Europe. The text underneath a black cross notes that one Enzo Cotroneo is "missing from the affection of his loved ones". It omits to say that he died in a midnight ambush just a few days earlier.

Cotroneo, the striker of the local football team, was driving his VW Golf down a wooded lane just outside Bianco when another car forced him over. Carabinieri say at least three people were involved in shooting him dead.

On the morning after he met his bloody end, Cotroneo was meant to have been at an appointment with detectives investigating the slaying of a prominent regional politician, Francesco Fortugno.

Fortugno, the deputy speaker of the regional parliament, was shot dead last October 16 as he walked into the town hall of nearby Locri. The killer, dressed in black and with his face obscured by a cap, followed him into the building and put five bullets into him before fleeing to a waiting car. The assassination was the 23rd murder in or around Locri in just 14 months; Cotroneo may have known something about the men who carried it out; his subsequent murder ensured he would never talk.

Visiting Calabria after the assassination of Fortugno, Italy's then interior minister blamed it on the local mafia, the 'Ndrangheta, which he said was "the most deep-rooted, the most powerful and the most aggressive of [Italy's] criminal organisations".

Just pause to consider that remark. We are talking about the homeland of the Mafia - Sicily's Cosa Nostra. Are the Italian authorities really saying that a criminal fraternity few people have heard of (and the name of which even fewer could pronounce) is now more of a threat than the world's most fabled "mob"?

Behind his desk at the National Antimafia Directorate on the cobbled Via Giulia, in the heart of Rome's historic centre, Enzo Macri gives a sigh. "We've been saying it for years," he says. Macri, himself a Calabrian, is the prosecutor colleagues say understands the 'Ndrangheta better than anyone.

Cosa Nostra, perhaps because of its links to the United States, and in no small measure because of the Godfather books and films, continues to exercise an irresistible fascination. It was demonstrated most recently by the publicity given to the arrest of its "boss of bosses", Bernardo Provenzano.

But the evidence suggests that, while the Sicilian Mafia, like the US Mafia, has been fading to a shadow of its former self, the little-known 'Ndrangheta (pronounced "en-drang-ay-ta") has been taking over as Italy's true public enemy number one and has become a criminal empire with global clout.

For a start, it is bigger than the Mafia. Most estimates put its strength at 6,000-7,000 men against 5,000 for Sicily's Cosa Nostra. But Nicola Gratteri, a prosecutor who has specialised in tracing the Calabrian syndicate's international ramifications, reckons the figure for the 'Ndrangheta is an underestimate. "Altogether in the world, I would say it has maybe 10,000 members," he says at his office in the regional capital, Reggio Calabria.

As with the Mafia, the 'Ndrangheta's tentacles have spread thanks to emigration from Italy. In the period running up to 1925, dirt-poor Calabria lost more of its population than Sicily and more indeed than all but two of Italy's 20 regions. There was another massive outflow of Calabrians after the second world war, with the result that there are large communities of Calabrian descent - and remote outposts of the 'Ndrangheta - in Latin America, Canada and Australia.

The links with Latin America have proved particularly important, for they have helped the 'Ndrangheta to become a leading player in the global cocaine trade. Gratteri estimates that 80% of the cocaine entering Europe today is brought in by Calabrian mobsters. "The 'Ndrangheta," says Macri, "represents the globalisation of Italian organised crime."

Despite the 'Ndrangheta's new-found international prominence, its origins, as with all Italy's organised crime syndicates, remain obscure. Its name, like many dialect terms in Calabria, seems to be of Greek origin. It has been variously translated as referring to courage, loyalty and nobility.

According to the FBI, the 'Ndrangheta was formed in the 1860s by a band of Sicilians exiled from their native island - an explanation that could mean the organisation grew out of the original Mafia. At all events, court documents in the latter part of the 19th century increasingly reflected the existence of organised gangs in and around the main centres of population, and in 1888 the prefect of Reggio Calabria received a letter from an anonymous informant alerting him to the presence of "a sect that fears nothing".

For almost a century, the'Ndrangheta remained a local phenomenon - an evil, but essentially containable brew of rural banditry, urban racketeering and extortion. Then, in 1975, the murder of a local godfather at Locri signalled the beginning of a gang war that would transform the organisation at the cost of some 300 lives.

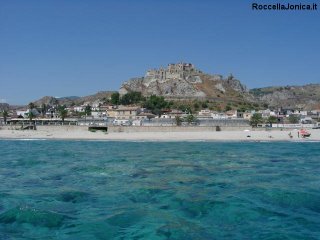

A young, rebellious and ultimately successful faction aspired to more profitable activities, notably the kidnapping of northern Italian businessmen. Their luckless victims were brought back to Aspromonte, the uplands that form the rocky, rugged heart of Calabria, and hidden in caves until their families or firms could get together the ransom. The profits were immense. Looking around for something in which to reinvest their new-found fortunes, the 'ndrine, or clans, of the eastern, Ionian coast hit upon narcotics. "They had the means with which to buy heroin from the Turks, hashish from the Moroccans and a variety of drugs and arms in the Lebanon," says Gratteri. "Then, at the start of the 1990s, there was a fundamental shift in the drugs market. Largely because of Aids, there was a sharp drop in the demand for heroin, which was accompanied by an equal sharp increase in rise in the demand for cocaine."

At first, the 'Ndrangheta gangs bought most of their cocaine from the then more powerful and pervasive Cosa Nostra, which already had links with the Colombian cartels. But it was not long before they were trading directly with the Latin Americans and by the end of the 1990s, the 'Ndrangheta had a network of local representatives established in Colombia.

"The Colombians prefer to deal with the Calabrians," says Macri. "They are much more reliable. They don't talk. And they pay on time."

In more than one respect, indeed, the 'Ndrangheta resembles the Sicilian Mafia as it once was. It is murderously querulous. The socalled second 'Ndrangheta war of 1985-91 cost more than 700 lives. Disputes even within small 'clans' can lead to public bloodbaths of a kind the Sicilian Mafia nowadays does its best to avoid. Six years ago, at the height of a dispute over control of the local drugs trade, a hit squad armed with pistols and a Kalashnikov cut down three alleged members of a rival faction, including 'Ndrangheta boss Salvatore Valente, 39, in the village of Strongoli near Crotone. A 73-yearold pensioner sitting on a bench was shot and killed in the crossfire of a three-way shootout in which a Carabiniere officer was also injured.

At the same time, the 'Ndrangheta is punctilious in its observance of old-fashioned underworld values. Just how old-fashioned those values can be was underscored in March with the arrest of the nephew of Giuseppe Morabito, known as Peppe Tiradritto (Joe Go-ahead), allegedly one of the syndicate's most feared godfathers. This nephew, Giovanni Morabito, gave himself up, admitting he had just shot and hideously wounded his sister, who was separated from her husband, after discovering that she was pregnant by another man. Bruna Morabito, who was shot in the face, was last reported by her doctors to have emerged from a coma but was only able to respond to them with nods.

This brutal, old-fashioned code of conduct has made combating this new mafia extremely difficult. The 'Ndrangheta, an exasperated Florida district attorney once said, is "invisible, like the dark side of the moon". Of all Italy's organised criminal groups, it has proved the most difficult to understand, let alone penetrate.

Like the others, it is known to initiate its members with rituals that vary from clan to clan and are meant to bind them to silence for life. As with the others, it has a system of ranks which in the case of some 'ndrine have a distinctly blasphemous ring: one of the most senior posts is that of Vangelo ("Gospel").

But whereas the Sicilian Mafia, the Neapolitan Camorra and the Sacra Corona Unita in Puglia are made up of "families" or "clans" that are really just gangs in which there is no need for the members to be related, the 'Ndrangheta is held together almost entirely by actual blood relationships. Most of its 'ndrine consist of extended families, often linked by marriage to form bigger units known as locali. "'Ndrangheta families have often arranged weddings to solder the links between them," says Gratteri. "There are families that have intermarried as many as four times in the 20th century."

Sons are not just expected, but in most cases required, to follow their fathers into the family business, receiving - sometimes at birth - the title of Giovane d'onore (young man of honour).

The overlap between criminal and family loyalties has made the 'Ndrangheta peculiarly impervious to the sharpest weapon in the Italian state's anti-mob armoury. Legislation introduced by the Italian government in the early 1990s made it easier for Mafiosi to turn state's evidence and become so-called pentiti (literally, penitents). The new arrangements have wrought havoc in the ranks of Cosa Nostra, but scarcely bruised the 'Ndrangheta. "A Calabrian mobster considering turning state's evidence has to come to terms with betraying maybe 200 of his relatives," says Gratteri.

"There have been 'Ndrangheta pentiti," says Macri. "But we have never had a boss turn state's evidence; they have always been low- to medium-ranking mobsters."

Another factor protecting the organisation is its structure, or lack of one. "Cosa Nostra is a pyramid," says Macri. "Cut off the top of the pyramid by arresting its leader and it has big problems. In Calabria, on the other hand, what you have is a federation. There are moments when some of the elements in the federation will come together, but it is more than anything for purposes of coordination. The 'Ndrangheta cannot be beheaded."

The Italian authorities reckon that the new mafia's turnover - estimated at €35bn (£24bn) a year - surpasses that of the entire annual output of Calabria's legal economy. But while there are rather more expensive cars than you might expect on the Ionian coast towns' potholed streets, there is scant evidence of the cash that is known to be flowing into Italy's poorest region. "In Calabria, there are billionaires who live like paupers," says Macri. "The young drug couriers make a show of their wealth. They wear Rolexes and drive BMWs. But the more senior members of the 'Ndrangheta, who are on the run, often live in caves in the mountains in conditions of genuine hardship."

"When they go up to Milan or abroad, the 'Ndrangheta families live it up," says Gratteri. "But back in Calabria they go to great lengths to disguise their wealth. I have been to houses that are not even painted on the outside, but which, inside, have onyx floors and antique furniture."

The Italian authorities have been remarkably sluggish in their reaction to the 'Ndrangheta, but then Calabria is poor, lacking in influence and a long way from Rome. "We have the richest and best-organised mafia in Italy and we're trying to tackle it without proper resources," says Nuccio Iovene, a senator for the formerly communist Left Democrats. "It's like Russia."

In the mob-ridden town of Lamezia Terme, he says, police patrols have had to be reduced to save petrol. "The police cars are in such bad condition that during a recent chase one of them caught fire."

The way the judiciary is organised does not help either. After they qualify, Italian judges and prosecutors are given their choice of postings. Those who come top in their exams get the first choice and those who finish near the bottom get whatever is left. "That's usually Calabria," says Senator Iovene. "It's considered a hardship post. So the moment they arrive, they put in a request to be transferred elsewhere. When Francesco Fortugno was killed, in Locri, a hotbed of 'Ndrangheta activity, the magistrate with the longest experience had been in the job for only six months." Fortugno's assassination - in the dying months of Silvio Berlusconi's government - finally jolted the state into action, however. The interior minister came down from Rome, as already mentioned, and announced a series of special measures.

But the murder also put a huge question mark over the future. There are signs that the 'Ndrangheta shrewdly anticipated Berlusconi's fall and began to shift the votes it controls to the left. At a regional election in April 2005, almost two-thirds of Calabria's electors voted for Romano Prodi's centre-left alliance, which took power nationally last month. Fortugno, a doctor, was a Prodi man. His assassination is thought to have something to do with the 'Ndrangheta's efforts to penetrate the local health authority. But there are some who fear it was also a way of sending a message to the people they expected to form Italy's new government.

The 'Ndrangheta has an unusually keen interest in politics at the moment, because of the plan to build a bridge over the straits of Messina to link Sicily with the Calabrian mainland. It stands to cream off millions of euros from the contracts that would be awarded.

Berlusconi's government wanted the bridge to be built. Prodi's team is split on the issue, partly because of fears that it could prove a bonanza for southern Italy's mobsters. "By killing Fortugno," says an investigator who has asked not to be identified, "they may have been sending a message to the centre-left: 'We have given you our votes. Now, we expect results'".